The history of the espresso machine is a tale of speed, pressure and the very Italian conviction that if something is worth doing, it’s worth doing to perfection. Without the concerted effort of coffee-obsessed Italian inventors, espresso as we know it wouldn’t exist.

At first, the modern-day espresso machine was an absolute beast of a contraption. So, how did it evolve into the sleek countertop machines we love and use today?

Read on for the full story.

Table of Contents

Why Espresso and Why Italy?

As anyone who’s familiar with the history of coffee knows, by the 18th century, it was Europe’s trendiest beverage. But there was a slight problem: brewing it took forever.

By the 19th century, cafe customers (many of them blue collar workers who relied on coffee to get going in the morning), began demanding faster service. As a result, coffee shop owners who couldn’t keep up began to lose business.

Enter the Italian obsession with efficiency and engineering.

At the thick of Victorian-era industrialization, inventors began applying steam power to everything from textile mills and factories to coal mines and engines. Coffee, which by now was at the heart of Italian life, was the next obvious target.

The goal wasn’t just to leverage steam power to brew coffee faster, but also to extract maximum flavor in the shortest time possible.

This was a major turning point in the history of the espresso machine. Italian cafes began serving coffee to standing customers at the bar (hence the term “espresso,” meaning both “pressed out” and “express” or fast).

But, there was another factor at play: Italian coffee leaned heavily toward flavor intensity.

Unlike the French, the Italians didn’t particularly enjoy large, leisurely cups. Instead, they favored small, powerful shots that delivered maximum flavor and immediate satisfaction.

The espresso machine solved this problem. It didn’t just speed up the brewing process, but fundamentally transformed what coffee could be.

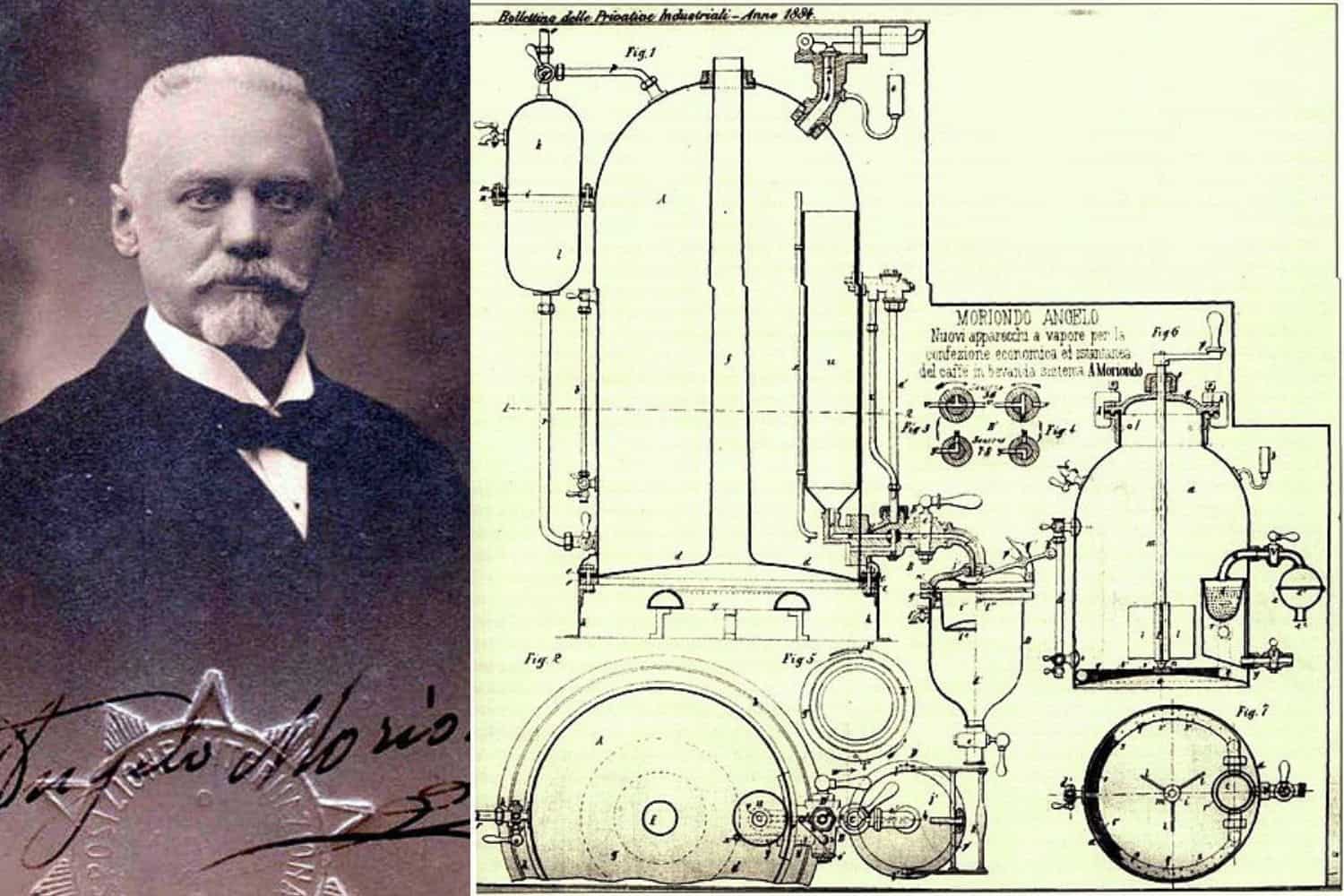

Angelo Moriondo: The Godfather of the Espresso Machine

The need for coffee innovation eventually fell upon Turin cafe owner and hotelier Angelo Moriondo, the godfather of the espresso machine.

Frustrated at customers fidgeting (and some leaving) while waiting for their brew, Moriondo had a lightbulb moment: what if he could use steam pressure to force hot water through coffee grounds at speed?

In 1884, he invented the answer and patented a “new steam machinery for the economic and instantaneous confection of coffee beverage.”

His machine was massive! At its heart, was a boiler-and-piston setup that could brew multiple cups simultaneously by pushing water and steam through a bed of coffee grounds. The best part was, it cut brewing to under a minute – revolutionary for the time.

However, the problem was that Moriondo’s invention was not an espresso machine perse, but a batch brewer. Furthermore, the coffee quality wasn’t consistent, a non-negotiable in thebest espresso machines. To add to this, his machine produced too much steam, often yielding bitter, over-extracted mud.

Still, Moriondo proved the concept: pressure plus speed equals espresso.

Despite debuting his invention at the 1884 General Exposition, he never commercialized it beyond his own establishments. However, Moriondo did something far more important: he lit the fuse.

Luigi Bezzera and Desiderio Pavoni: Early Innovators

Moriondo had given the world the blueprint; someone else needed to perfect it.

That someone was Luigi Bezzera, a Milanese manufacturer. He saw the fundamental flaw in Moriondo’s invention and improved on it. In 1901, he contributed to the history of the espresso machine with the first true single-serve espresso brewer.

His design used a boiler to generate steam pressure. This pressure forced water through a portafilter holding a single serving of coffee grounds. Individual espresso shots meant that a barista could control each cup’s quality. What’s more, the brewing time dropped even further, to an optimal 30 seconds.

Still, this machine stayed under the radar. The problem? Bezzera was an inventor, not a marketer.

That job would fall to Desiderio Pavoni, an entrepreneur who saw gold in Bezzera’s patent. In 1905, he bought the rights to the machine and immediately got to work refining it. Notably, he added a pressure-release valve (crucial for preventing steam explosions), improved the grouphead design and introduced the first steam wand for frothing milk.

More importantly, Pavoni actually manufactured and sold these machines, debuting his Ideale at the 1906 Milan Fair to massive acclaim.

As a result, Pavoni’s commercial success turned espresso from a cafe curiosity into an Italian institution. By the 1920s, espresso dominated Italian coffee culture, setting the template for modern coffee.

Other Manufacturers Emerge

Pavoni’s unbridled success kicked off an arms race of espresso innovation in Italy. All over the country, engineers scrambled to fix the machine’s most glaring issue: steam pressure maxing out at around 1.5 bars.

This pressure mattered because coffee continued to extract slowly, coming out with a bitter edge that no amount of sugar or cream could fix. Something had to give.

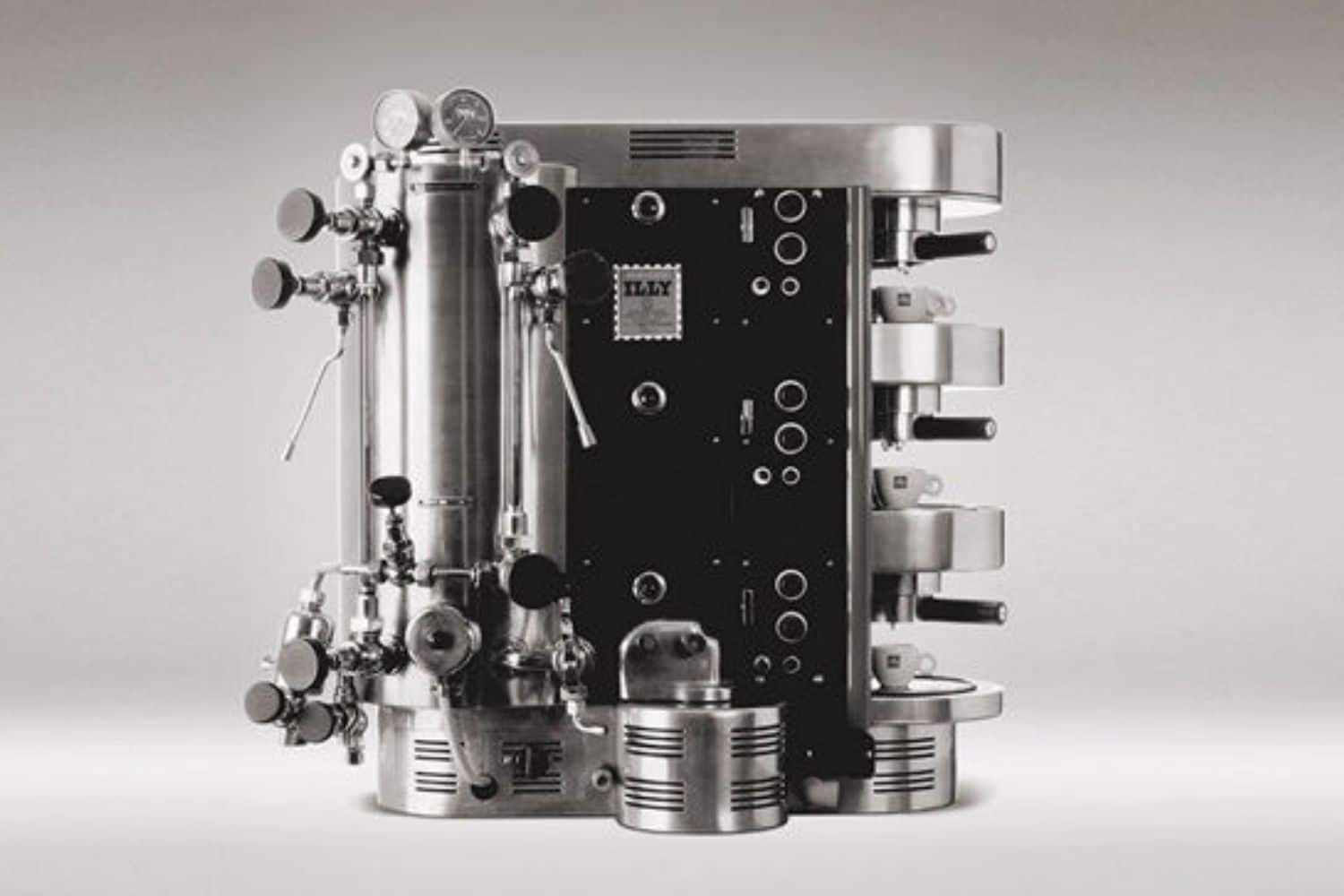

In 1935, Francesco Illy (yes, the famous Illy), debuted the Ileta, an espresso machine that swapped steam for compressed air. Illy’s invention achieved more consistent pressure and lower brewing temperatures. Thus, this improvement yielded cleaner, less bitter espresso shots.

It was genius, really, except that air compressors were expensive, loud and complicated. Most cafe owners stuck with what they knew.

The 1920s and ’30s saw espresso machines become cafe centerpieces – towering, theatrical and deeply tied to Italian national identity. Mussolini’s government even promoted espresso culture as a symbol of Italian efficiency.

This prompted some manufacturers, like Victoria Arduino, to focus on aesthetics and usability. Machines like the Eagle One Prima, still maintain that stylish art deco philosophy today.

But despite all the glamor and incremental improvements, nobody had cracked the fundamental problem: how to generate real pressure without steam. That breakthrough was waiting in the wings, and would come courtesy of Achille Gaggia.

Achille Gaggia and the Birth of the Modern Espresso Machine

If Moriondo lit the fuse and Bezzera and Pavoni built the foundation, Achille Gaggia detonated the bomb that created espresso as we know it today.

A Milanese cafe owner, Gaggia was fed up with the burnt, bitter coffee that steam-pressured espresso machines churned out.

The problem lay in physics. Steam could only generate about 1.5 bars of pressure, and it heated water well past the ideal brewing temperature. Patented in 1947 and commercially launched in 1948, Gaggia’s solution was brilliantly simple: ditch the steam entirely.

This machine changed the history of the espresso machine entirely. Because it used a manual spring-loaded piston and lever, all a barista had to do was pull the lever down. This set in motion a powerful spring that would force hot (but not superheated) water through tightly packed coffee grounds.

Crucially, it would do so at 8-10 bars of pressure – nearly six times what steam could achieve but at lower temperatures.

The result was a smooth, single-serve espresso coffee, extracted within 25-30 seconds, and topped with a golden foam nobody had seen before. Gaggia called it crema, and it became espresso’s signature.

The impact of Gaggia’s invention was seismic. His machine produced coffee that actually tasted good! Furthermore, it was sweet, full-bodied, complex and aromatic.

Espresso Travels the World

Gaggia’s machine didn’t just improve espresso; it made it portable, reliable and crucially, exportable. As Italian emigrants scattered across the globe in the post-war years, they brought along espresso machines, becoming ambassadors of Italian identity in the most unlikely places.

In Australia and New Zealand, waves of Italian immigrants transformed these sleepy, tea-drinking Commonwealth realms into coffee-loving societies in the 1950s and ’60s. A distinct Australian coffee culture emerged with the flat white and long black defining the cafe culture.

Meanwhile, American GIs stationed in Italy during World War II returned home with espresso cravings they couldn’t shake. This kicked off North America’s first espresso wave in the 1950s. However, espresso culture remained niche here until Starbucks catapulted it in the 1980s.

In East Africa, Italian influence left a complex legacy, but one undeniable gift: espresso machines in Eritrea and Ethiopia. Today, art deco cafes in Addis and Asmara still serve macchiatos, brewed on Gaggia lever machines from the 1940s.

Even Austria, already famous for its own 18th-century coffee houses, couldn’t resist. Vienna initially resisted (espresso felt too fast, too aggressive). However, Italian espresso machines eventually infiltrated the city in the 1950s, sitting awkwardly alongside traditional Viennese coffee recipes.

Everywhere espresso went, the espresso machine followed. It wasn’t just the coffee that fascinated people, but also the theater. Chrome and brass gleaming under cafe lights, the rhythmic hiss of steam and the unmistakable aroma of fresh-brewed espresso beans drew people in.

Coffeeness Medium Roast Espresso

Well-balanced with chocolate & hazelnut notes

Freshly roasted in Brooklyn

Very low acidity

La Faema E61: The First Electric Espresso Machine

Despite espresso’s global success, there was still one massive problem: making it could get exhausting. Gaggia machines at the time required baristas to manually pull every single shot. This sounds romantic, but try pulling 200 plus espresso shots a day!

The answer to this problem came with Carlo Ernesto Valente and his company Faema. In 1961, he unveiled the E61, the first electric-pump-driven espresso machine.

Instead of human muscle or spring-lever tension, the E61 used an electric rotary pump to generate consistent 9-bar pressure at the flip of a switch. No more pulling of levers, and no more variation between espresso shots.

The E61 also introduced a heat exchanger that kept water at optimal brewing temperatures while simultaneously providing steam for milk. It also featured horizontal groupheads that became the industry-standard design you still see today.

The impact of these improvements on the history of the espresso machine is undeniable, leading to a marked improvement in workflow and overall efficiency.

Subsequent Developments and Innovations

The legendary Faema E61 changed the history of espresso. Its electric pump system and heat exchanger design were so fundamentally sound that nearly every manufacturer since has riffed on Valente’s original blueprint.

La Marzocco was one of the first to bite. Founded in Florence in 1927, they had been making lever machines for decades. However, they immediately recognized the E61’s genius. In 1970, they released the legendary La Marzocco GS/2. This machine took Faema’s dual-boiler concept and upgraded it with independent boilers for each group head.

This meant baristas could brew espresso and steam milk simultaneously and, importantly, at different temperatures. As a result, La Marzocco’s commercial machines became the gold standard. One look at the La Marzocco Strada and you’ll see why.

Founded in 1936, Nuovo Simonelli followed suit with their Aurelia line in the 2000s. They added programmable shot volumes and temperature profiling, enabling baristas to save recipes, adjust extraction parameters on the fly and achieve insane levels of precision.

Proportional-Integral-Derivative or PID controllers represented another quantum leap. These digital temperature regulators, which began appearing in high-end machines in the 1990s, could maintain brewing temperatures to within a degree or two, eliminating wild swings.

Then came the post-third wave disruptors. Synesso, founded in Seattle in 2004, pushed the boundaries even further with their Cyncra and Hydra models. These machines offered per-group temperature control, pressure profiling and real-time adjustment during extraction. Baristas could now manipulate pressure curves mid-shot, unheard of before.

Other innovators soon joined the wave. Slayer introduced flow control paddles that let baristas manually adjust water flow during extraction. And Victoria Arduino integrated gravimetric technology, weighing the liquid espresso output in real-time to stop extractions at precisely the right moment.

What all these machines shared is the E61’s DNA: electric pumps, heat exchangers or multiple boilers and horizontal groupheads. They showcased the fundamental principle that consistency plus control equals excellence.

Espresso Machines Today

Modern espresso machines exist along a spectrum of automation. As such, different types of espresso machines reflect different philosophies, especially when it comes to balancing human skill and mechanical precision.

Fully manual lever machines, direct descendants of Gaggia’s original design, remain the purist’s choice. Here, the barista controls every variable: pulling a lever to generate pressure, feeling the resistance of the coffee puck and sensing when to ease off.

La Pavoni continues to produce beautiful lever machines that look like they belong in a mid-century Italian café. ROK Espresso is also making waves with their all-manual British machines. And portable espresso machines from Outin and Flair are becoming ever more popular.

Next, semi-automatic machines. These are the choice for most serious coffee enthusiasts. They automatically maintain consistent temperature and pressure, but let the barista control when to start and stop the shot.

Brands like La Marzocco, Synesso and Slayer dominate the commercial semi-automatic market. At the other end of the spectrum, Rancilio, Gaggia and Breville top the home market.

In contrast, super automatic machines handle everything, from grinding and tamping to shot timing. In busy commercial settings, where consistency is as essential as craftsmanship, machines from brand giants Jura, Franke and Schaerer dominate. DeLonghi and Phillips are popular in the domestic market.

But perhaps the most significant development in the recent history of the espresso machine is the rise of the prosumer espresso machine. This brings professional-grade capabilities to home kitchens, blurring the line between cafe and domestic settings. It’ll often boast dual boilers, rotary pumps, PID controllers and, importantly, the legendary E61 group head.

Brands like Rocket Espresso, ECM, Profitec and Lelit produce efficient but easy-to-use prosumer machines that would have been unthinkable in a home context twenty years ago.

Meanwhile, companies like Decent Espresso are pushing things even further. Their smart coffee machines let users program pressure, flow rates and temperature throughout extraction, using a computer tablet. With these WiFi-enabled machines, you can turn each espresso shot into a customizable experiment!

Espresso Coffee Pod Machines

Lastly, it would be intellectually dishonest of me not to discuss the elephant in the room: pod or coffee capsule machines. Nespresso, Keurig and their numerous imitators have made espresso consistent and fast. Pop in a pod, press a button and thirty seconds later you have something approximating espresso.

I must say, I’m opposed to them in principle. Not because they lack sophistication (though, to me, they do). My opposition is more fundamental: pod machines represent the complete surrender of craft to convenience.

They also reduce espresso to a mere commodity, erasing the variables that help you understand your equipment and your beans better. Not to mention, they wreak havoc on the environment.

Yet, I recognize that for millions of people, pod machines have been a gateway, an introduction to espresso coffee culture that might not have happened otherwise.

I hope, in time, a percentage of these coffee drinkers will graduate to something with more soul. That’s my optimistic view, anyway.

Final Thoughts: The Future of Espresso Machines

So, what comes next? Going on the history of the espresso machine and current trends, the future looks cautiously exciting. Why cautiously? Let me explain.

The espresso machines of 2050 will likely feature AI-driven extraction profiles that adjust brewing variables in real-time based on bean moisture content, grind size and even ambient humidity. These machines will likely learn your preferences through hundreds of micro-adjustments, achieving personalization profiles impossible through human programming.

I also see espresso machines with quantum-stabilized water temperature (doing away with crude heating elements) and gravitational-field-controlled pressure (doing away with pump pressure). Heck, some may even have stasis chambers for peak bean freshness!

But then, would these machines still brew real espresso? Or, like with Star Trek replicators, just a very good simulation? That’s the stickler.

I’m still gunning (and hoping) for something simpler. I pray we get beautiful but efficient, manual-lever, semi-automatic or fully automatic machines that preserve espresso craft, but in an increasingly automated world, do so efficiently.

Do you see a fully automated future for the espresso machine or a return to the glorious basics? Drop your views below, I’d love to read them!

History of Espresso Machines FAQ

Angelo Moriondo invented the original espresso machine in 1884, in Turin, Italy. However the first commercially successful espresso machine came from Milanese manufacturer Luigi Bezzera in 1901. It used steam pressure to force hot water through coffee grounds, producing a concentrated shot in under a minute.

They didn’t. Espresso as we know it didn’t exist before the espresso machine. Italians drank regular brewed coffee from a moka pot, percolator or Turkish coffee maker.

A traditional espresso machine is a lever-operated machine, like those Achille Gaggia popularized in 1948. These machines use manual lever pressure to force water through a bed of coffee grounds at around 9 bars of pressure.